“Ain’t No Valley Low Enough” to Keep Humans from Mining the Seabed’s Critical Minerals: The Realities of Deep-sea Mining and Indigenous Connections to the Seafloor

11 Februari 2026agnes

By Bobbie Chew Bigby (Cherokee Nation)

While the current state of the world on land may seem chaotic and unsettling, news from beneath the waves and across the oceans is often just as confronting. Whether we are talking about impacts to marine biodiversity due to sea temperature rise and related acidification, microplastics and pollutant contamination, or problems of overfishing, our planet’s waters and marine life have seen levels of harm parallel to what humans have inflicted on our land habitats. A recent study by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, found that when ocean impacts are included in the costs of climate change, the total economic costs of harm double. And yet in spite of this economic rationale for protecting and sustaining our marine environments, for some the deep-sea beds across the world’s oceans have become the next new frontier for mining. For some, promoting the solution to climate change as the need to turn towards “green” energy transitions that favor electrification over carbon-based technologies, this “blue” mining frontier holds deep riches and resources that are urgently wanted.

The existence of critical minerals on the seabed floor, including nickel, cobalt, copper, and manganese, among others, has been known about since the 1870s. It was during that period that the British HMS Challenger exploration ship surveyed certain areas of the world’s oceans and lands and came across what looked like lumps of black rock from the seabed floor. These lumps of rock would become known as “nodules” and, when analyzed more closely, were found to contain high levels of minerals, particularly cobalt and nickel. Beyond these polymetallic nodules, critical minerals can also be found in and around seamounts and hydrothermal vents. By absorbing minerals from the seawater and gradually growing around pieces of rock or other organic matter, these polymetallic nodules eventually precipitate these key metals.

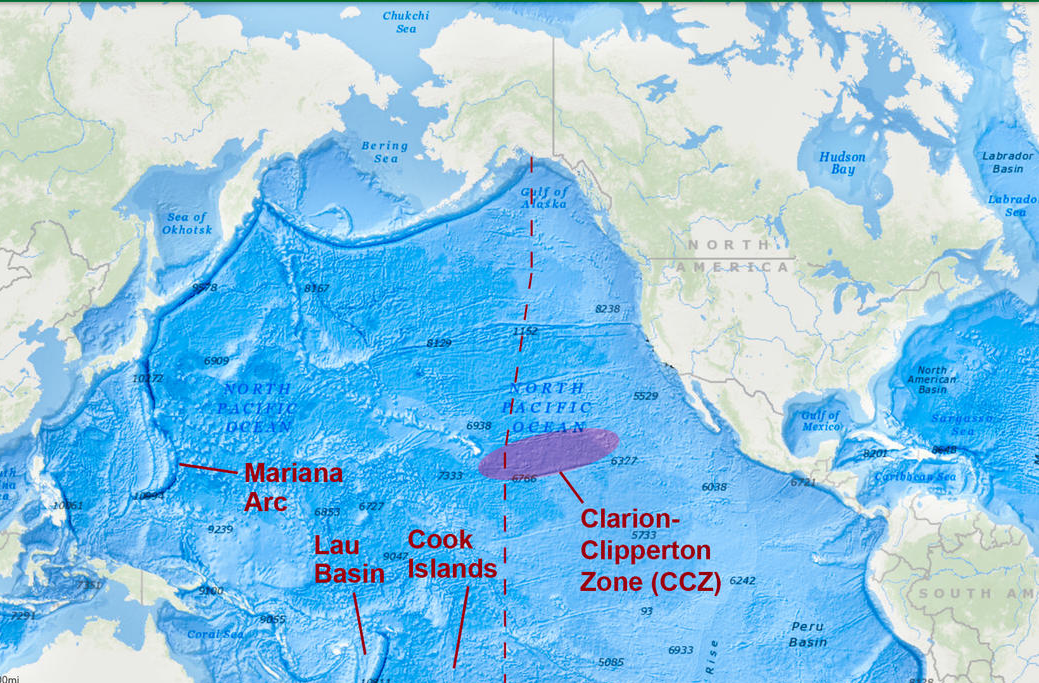

One of the areas that is best known for high concentrations of these critical deep-sea minerals is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a nearly two million square mile area of seabed midway between Mexico and Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean. While the CCZ represents only about 1% of the globe’s total seabed mass, it is a notable source of critical minerals, with some studies estimating that the area has more cobalt and nickel than all other land-based mines combined. Within the CCZ, nine protected areas are off-limits to mining and extraction activities. Yet these protected areas do little to reassure some maritime Indigenous stewards, scientists, and marine conservationists about the potential risks of mining in the deep reaches of the ocean, where it is estimated that over 8,000 species live in the CCZ alone.

A map depicting the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean. Credit: Wikimedia, USGS

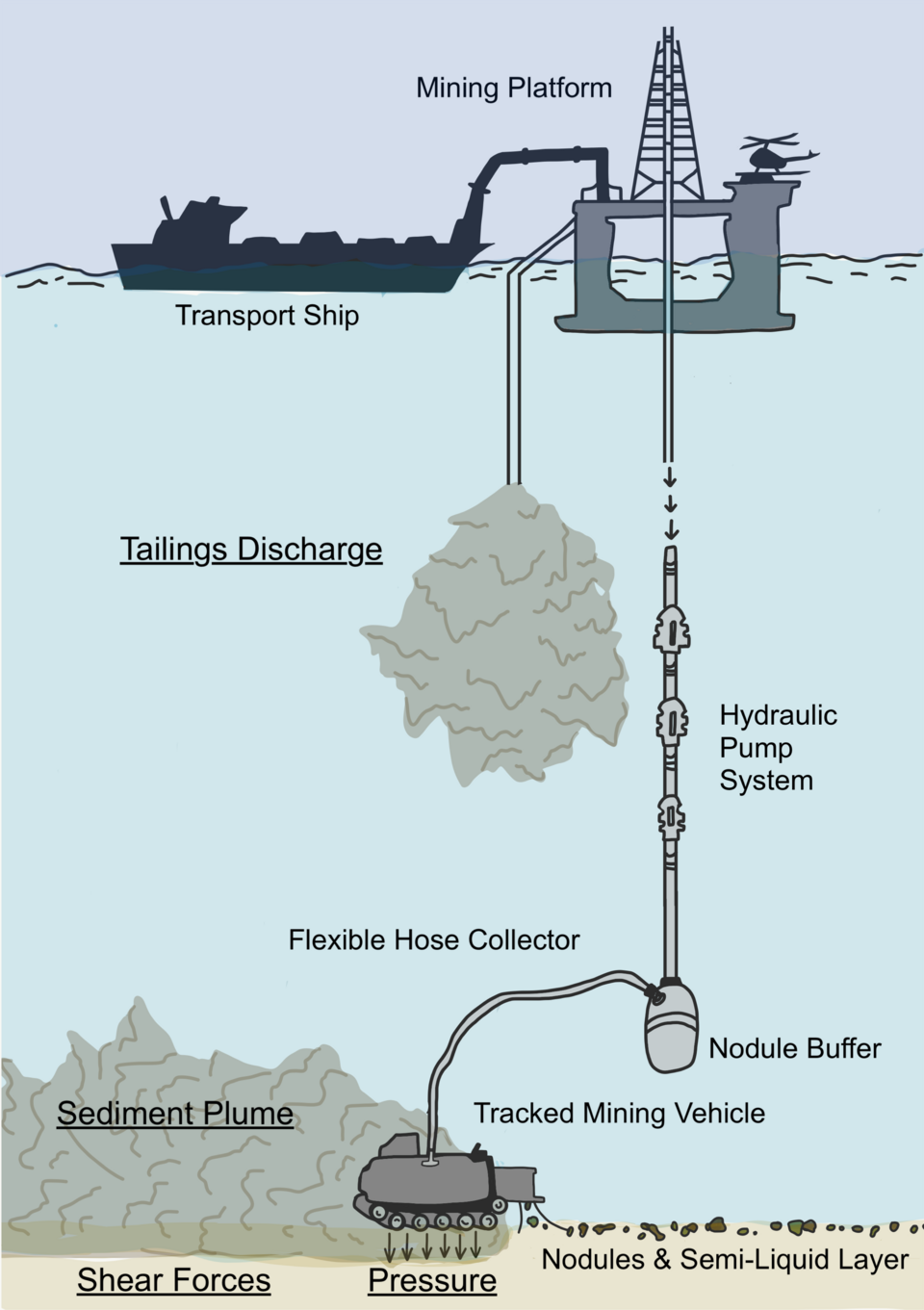

Much like land-based mining and extraction activities, heavy machinery and infrastructure is also required to access the critical minerals found throughout the ocean floor. Using various forms of deep-sea robots and box core rigs, this machinery assists in the “harvesting” of nodules by vacuuming them up into tubes that pump the mineral clumps onto boats. In 2017, the Belgian company Global Sea Mineral Resources was the first to put a robot on the seafloor. Since that time, other companies representing countries across the globe have also been developing machinery to extract these nodules in the most cost-effective way, yet often with little regard for the marine life of the deep oceans. To date, no country or company has been able to maintain mineral extraction at a commercially viable scale, even though efforts are ongoing.

On the one hand, proponents of deep-seabed mining assert that underwater mining avoids some of the most contaminating activities often seen with traditional land-based mining. Advocates of this ocean mining highlight reduced carbon emissions, given there is no need for blasting in the mining process, as well as the elimination of sulfidic tailings ponds that can often leach heavy metals into the groundwater and soil. On a larger scale, this drive for deep-sea mining is also deeply interwoven into larger conversations around the climate and shifts away from carbon-based energy sources. These advocates of deep-sea mining, including Canada-based The Metals Company, among others, frequently argue that the solution to the climate crisis lies on the ocean floor, where the critical minerals necessary for the energy transition are ours for the taking.

A schematic showing how nodules are “harvested” from the seabed floor using heavy machinery and the resulting tailings and sediment plumes. Credit: Wikimedia, MimiDeepSea

Yet a careful listen to any of these ideas about the ocean is based on a problematic premise—namely, that the deep ocean is devoid of life; that it is a big, dark wasteland of no use to humans unless we figure out how to mine it. What looms over this contested form of extraction is not simply an outlook that prioritizes human utilitarian needs over all other lifeforms. This type of extraction would also seem to be premised upon a lack of information and deep ignorance about this other part of our planet. After all, it is a frequently touted fact that more of the solar system has been explored, probed, and mapped in comparison with studies of the floor of our oceans that cover roughly three-quarters of planet Earth. A 2018 study by the National Centers for Environmental Information estimates that over 80% of the world’s oceans remain unmapped and unexplored.

For researchers and marine stewards who have focused on monitoring the impacts of seabed mining, concerns are growing as studies continue to examine observed and potential impacts. While there are no carbon emissions associated with land-based rock blasting, the machinery used on the seabed floors introduces significant sediment plumes, noise, and light to unique ecosystems that function with low oxygen levels and in the dark. Given the depth of these marine ecosystems at more than three miles underwater and the lack of study to date, scientists assert that these areas are home to creatures and new species that we have not had a chance to understand, ranging from mollusks and fish to sponges, octopi, and other lifeforms. A further concern related to mining is that many of these deep-sea creatures live on or around the nodules that are being swept up and vacuumed. Additionally, organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund have asserted that sea-based mining is much harder to monitor and regulate than extraction activities on land. These organizations opposed to seabed mining often advocate for metals recycling and recovery from tailings as an important first step and alternative to opening up extraction in places we are unfamiliar with. Given these extreme risks, as of 2025, 40 countries have called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining.

Against these massive risks, the fate of seabeds under the current system of international governance seems equally unclear. Under the UN’s Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) established in 1958, all coastal countries retain sovereignty over their seabeds extending to a 12-mile radius. Extending another 200 miles is the country’s “Exclusive Economic Zone,” where a country retains jurisdiction over economic activities, including mining, oil and gas production, and fisheries, among others. The seabed floors beyond these zones are considered to be ‘international waters’ and fall under the jurisdiction of a UN agency known as the International Seabed Authority (ISA). The ISA comprises 168 member countries, including the EU. For a company or country to engage or extract from what are designated as “international waters,” they must apply for an exploration permit from the ISA. In the Clarion Clipperton Zone, 19 countries have applied for and received licenses for mining exploration activities, with China holding the most licenses. To date, the United States holds none.

Even more surprising than that, since 1994, the US has not had a seat at the table with the International Seabed Authority (ISA). Stated more accurately, perhaps, the US has chosen not to have a seat at this table, given partisan opposition among some US Senators in not wanting to engage with this UN body. Given the US stance in not being a party to the UN Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the US is not eligible to apply for these licenses, nor is it working alongside other member nations of the ISA to create a much-needed regulatory framework that would put guardrails on this industry.

In this race to mine the ocean, participants have come from countries large and small, from across both the Global North and Global South. Because the ISA had intended to grant equal access to countries deemed both “developed” and “developing” alike in these seabed activities, one of the key ways that developing countries, and Pacific island nations in particular, have been involved in this industry is when they have been approached to partner with a mining company. An important example of this is the Canadian corporation mentioned before, The Metals Company—one of the primary companies engaged in this industry—and their partnership with the nations of Nauru, Tonga, and Kiribati. This race for deep-seabed minerals is also not confined to the Clarion Clipperton Zone alone, as shown by recent efforts to explore mineral deposits by countries ranging from Japan to the Cook Islands. And deep-sea mining is not relegated to the Pacific Ocean, either, as exploration ambitions off the Arctic coast in Norway and licenses held by India to explore the Indian Ocean demonstrate.

Against this complicated backdrop, Indigenous communities and leaders, island Nations, marine conservationists, and others are trying to navigate the massive challenges posed by deep-sea mining—from its predicted harms for marine life and cultural lifeways to the economic, environmental, and geopolitical consequences of this industry. Listening to the viewpoints from Indigenous Elders and leadership from the Cook Islands and Hawai’i across the Pacific helps to shed light on why deep seabed mining is not straightforward in its potential benefits, even as the cultural harms and other risks loom large.

The Cook Islands comprise 15 islands in the South Pacific, located between Hawai’i and Aotearoa (New Zealand). While these islands are known for their unique marine biodiversity and the tourism industry that this biodiversity supports, the Cook Islands have increasingly become involved in exploring deep-sea mining possibilities. As asserted over recent years, Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown stands in support of seabed mining and has long been a promoter of the industry. From his vantage point, the threats from climate change and sea level rise to his island nation are real. Moreover, the promised climate funding from larger, developed countries to nations such as the Cook Islands to build climate resilience and adapt to devastating conditions has been insufficient and has not arrived quickly enough. In the face of these stark realities tied to carbon-emission legacies, PM Brown sees the benefits of deep-sea mining in both fueling the energy transition and providing his home islands with financial resources to manage challenges from climate change.

.jpg)

Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown. Credit: Wikimedia

Other Cook Islanders, however, do not necessarily share this enthusiasm for the possibilities of deep-sea mining. For some, there is a concern that the unknown impacts of this deep-sea extraction could harm the Islands’ existing primary economic activity of tourism. For others, the traditional values that Cook Islander culture has placed on relationships humans have maintained with the oceans are paramount. Islanders such as Teina Rongo, a Cook Islander Marine Biologist, warn that, “Our ancestors respected that ocean. We fear the ocean, and therefore, in a way, it’s protected. We were never about exploring the bottom of the ocean because our ancestors believed it was a place of the gods. We don’t belong there.”

In the heart of the Pacific Ocean, Indigenous Kanaka Maoli (Hawaiian) elder Solomon Kaho’ohalahala of Lāna’i agrees with these traditional sentiments and expands upon them. In recent years, he has served as one of the key global voices in opposing deep-sea mining. Countering the long-held mainstream assumptions that the oceans are vast places of dark and empty nothingness where anything is open for the taking, Kaho’ohalahala asserts that, “[The ocean] is not a place that has been vacant. It is not a place of nothingness. The people of Oceania have traversed this ocean for millennia. We are the people who understand the intimacy of the ecosystems of these areas. It is our country. It is our home.”

Solomon Kaho’ohalahala offers a traditional chant to a gathering involving Greenpeace International, among other parties. Photo by IISD/ENB: Diego Noguera.

In this interview with Kaho’ohalahala, he links this respect for the oceans and deep-sea with the creation chant of the Kanaka Maoli people, called the Kumulipo. Kaho’ohalahala points out that it was Queen Lili’uokalani, a champion of Indigenous Hawaiian sovereignty, who translated this chant into English and put a spotlight on its importance for Kanaka Maoli. Kaho’ohalahala continues that,

“The Kumulipo is not just a chant. It has within it things we need to contemplate and that are necessary for us to know. It is helping us to understand that we have a genealogy that is part of our culture—and it is one that speaks of our creation and that takes us into the depths of the deepest part of the ocean… [the chant] tells us we come from the deep ocean and [about] the creation of our eldest ancestors, Uku Ko’ako’a (the coral polyp). This is our mo’okū’auhau (genealogy). This is our understanding of who we are and where we come from…

Therefore, how is it that we would allow a process to intervene and intrude into our place of creation for the purpose of extraction? The extraction is being justified to [support] the green economy, but at no time did anyone consider that we have a connection to this place. So I am intervening, and I am saying that we have a cultural connection to this place.”

Kaho’ohalahala’s efforts to not only to speak out against the dangers of deep-sea mining, but to awaken all people to the ways in which Kanaka Maoli people have and will always be connected to the depths of the ocean have not gone unnoticed. He has been a leading voice at meetings of the ISA for Indigenous peoples and others concerned with the potential dangers of this extraction. In 2024, he was also recognized by the Blue Marine Foundation with a Lifetime Achievement Award for his decades of advocacy for and stewardship of the ocean.

While the voices of Island stewards such as Teina Rongo and Solomon Kaho’ohalahala may not always be as loud and as prominent as many of the debates surrounding “green” energy transitions and deep-sea mining, the insights that they open up about human connections to the deep-sea floor are important beyond measure. In areas of the world such as our deep-sea ocean beds that western science admittedly knows so little about, it is imperative for industry, governments, and science alike to stop and listen to those who not only understand these places but respect and care for them.

–Bobbie Chew Bigby (Cherokee) is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, where she researches the intersections between Indigenous-led tourism and resurgence. This article is part of a series that elevates the stories and voices of the Indigenous communities and land defenders impacted by mining for transition minerals.

Top photo: Pollymetallic nodules on the bottom of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone seafloor. Credit: Wikimedia, Mister Pommeroy.